Blowing the Whistle on Argentina

by Ingrid Gnaedig

If you were to ask a person in the street today what their first thought was when considering Argentina and football together, chances are they would probably mention Lionel Messi or Diego Maradona. If they follow the sport more closely, they might mention how many FIFA World Cups the national team have won (two), or even that Argentina hosted and won the tournament in 1978. However, they probably would not tell you that this monumental event in Argentina’s football history served as an attempt by its military government to conceal from the world the many atrocities it comitted.

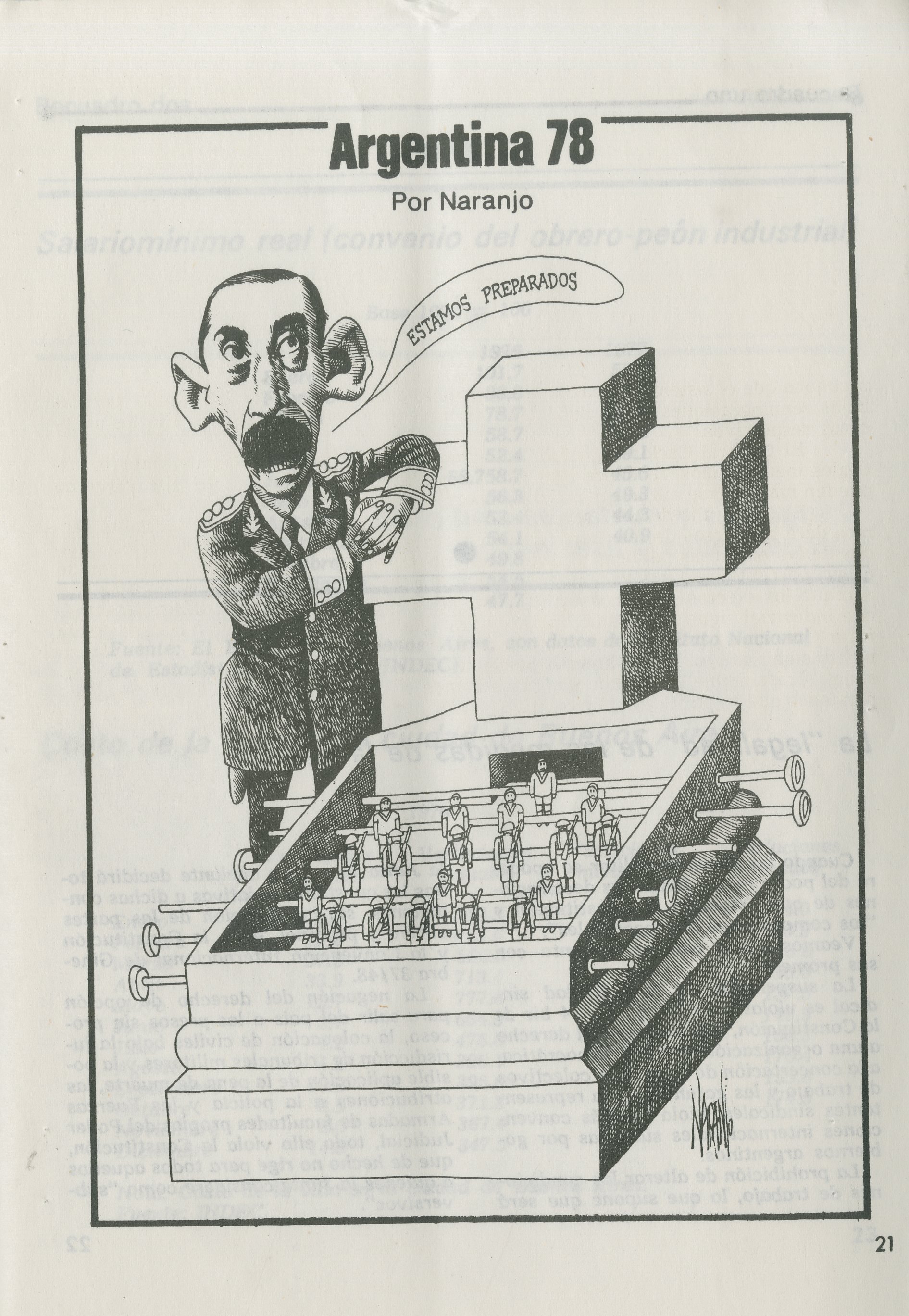

This is exactly what is denounced by the cartoons created for the UK’s Argentina Support Movement as well as the Comisión Argentina de Solidaridad (Argentine Solidarity Commission of Mexico). Indeed, on the cover of the pamphlet created by the British organisation we can see the figure of Jorge Rafael Videla, the leader of the military junta, painting over a ball attached to a chain, transforming it into a football. This image clearly alludes to the desire of the junta to use the World Cup as a means of brushing over and distracting from their oppressive regime. Similarly, although perhaps more explicitly, Mexican artist Naranjo’s cartoon in the second image alludes to violence and death caused by the military regime, as his reference to the World Cup is a foosball table built into a tomb, with the figure of Videla leaning against it saying “we are ready”. Yet there is no precision as to what they are ready for – the World Cup itself? Or to respond to any potential protests or opposition with repressive violence? The uncertainty created by this veiled threat reflects the general atmosphere of fear in Argentina at the time. Ultimately, the idea of dissimulation in the cartoons is a very important one, as it reflects the junta’s desire to make Argentina a country like any other, able to host and engage in international sports events as a means of gaining international legitimacy.

However, as demonstrated by the pamphlets, the oppression and violence carried out by the military government was undeniable. Indeed, despite being painted over, the massive ball and chain dominates the page, as well as the figure it is tied to, who is also forced to hold it up, like a condemned Atlas, forced to hold up the world. This image is strengthened by the other two figures on all fours that are serving as step-stools for the Videla figure. What is more, there is a stark contrast between these kneeling men and the single standing figure, the dictator, who is also the only character smiling while the others show sad faces, thus reinforcing the inequality and extreme diversity of situations within Argentine society.

Overall, these three civilian figures represent the Argentinian people buried under the weight of the junta’s repression, which is embodied by the Videla figure as well as the ball and chain. In Naranjo’s cartoon the violence is alluded to by the various military figures, which is first and foremost embodied by the caricatural Videla, whose enlarged figure dominates over the rest of the elements of the picture. This imagery is also in the finer details of the piece, where we see that one of the teams within the foosball table consists of soldiers, who make up every other row, thus seemingly imprisoning the opposing team. These two elements only serve to emphasize the constant presence of the military in Argentinian society. Moreover, like Videla’s aforementioned promise of readiness, the tomb and its imposing cross serve as a promise that any resistance will be met with merciless persecution, ranging from torture to death.

Yet despite the junta’s hopes that its violence could be hidden, the undeniability of the oppression hinted at in the cartoons extended into an international awareness. Indeed, the simple existence of international organisations of solidarity with Argentina such as the UK’s Argentina Support Movement and the Comisión Argentina de Solidaridad (Argentine Solidarity Commission of Mexico), prove that knowledge of the junta’s actions had spread around the world. However, by referring to the World Cup specifically, solidarity organisations sought to divert the audience’s attention away from the sport to the reality of the Argentine dictatorship, in the aims of spreading awareness and extending solidarity. Moreover, from a broader perspective, football is a sport that has a mass following and a well-established community anchored in a sense of solidarity, which presents a major opportunity for any campaign. In 1978, the World Cup was broadcasted in over 70 countries, providing a massive platform from which to spread awareness from. Moreover, the tournament already raised international controversy due to concerns surrounding Argentina’s political context, and was considered by critics to legitimise the military junta. This made the efforts of solidarity organisations all the more important as it shared key facts and figures with audiences that may not have been interested previously. For example, the cartoons studied in this essay are part of pamphlets that provide insight into the backdrop of Argentinian World Cup preparations, as well as data on the economic and political context. The Argentina Support Movement’s choice to integrate facts and figures as a part of the cover alongside the drawing shows the desire to present the urgency of the situation in Argentina, particularly the human cost. Finally, it is important to bear in mind that these organisations had the advantage of security that local and foreign journalists in Argentina at the time of the World Cup did not have.

Overall, the cartoons for the Argentina Support Movement and the Comisión Argentina de Solidaridad were a means of calling attention to the situation in Argentina beyond the World Cup, denouncing the atrocities committed by the military junta. Moreover, they reminded international audiences that the most important team to root for and support was not made up of football players but rather the Argentinian people, in their struggle against repression. A sentiment that would resurface decades later, when discussing the 2022 FIFA World Cup set in Qatar.